P. J. Collins

(Originally published in Counter-Currents,

October 23, 2018.)

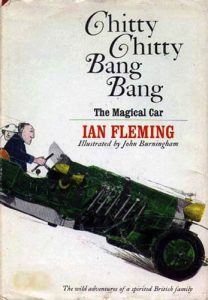

Surely, Ian Fleming’s final book, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, is also his finest work of fiction. Published 54 years ago this month, shortly after Fleming’s death, it is visibly superior to the James Bond books in so many ways.

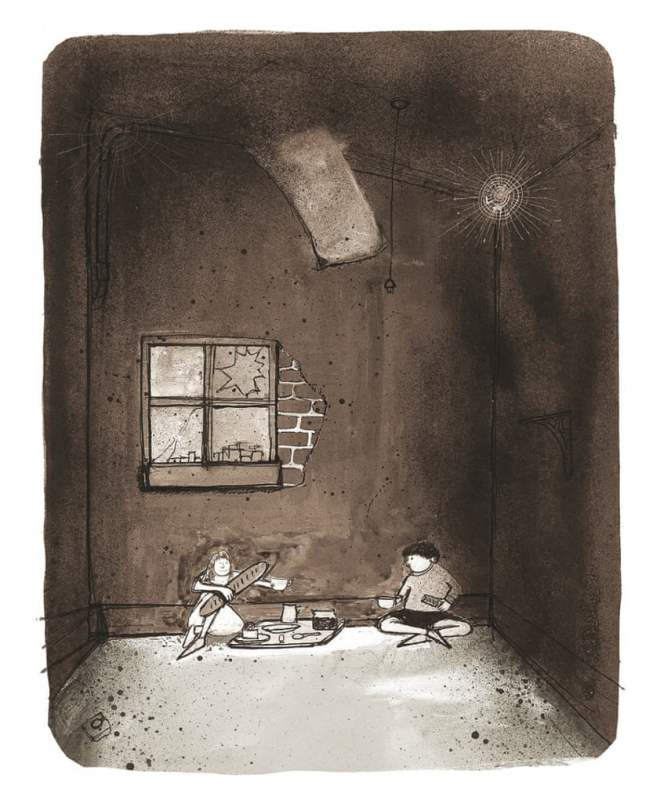

For one thing, it has pictures. Fleming and his editors struggled long and hard to select the right illustrator. The drawings by the illustrator who was eventually selected, John Burningham, are note-perfect and meld perfectly with the text. They’re drawn in the sloppy-intuitive school popular among British illustrators of the era (see also Paul Hogarth, Ronald Searle, and Ralph Steadman), and are almost entirely in black-and-white, or rather black-and-greys.

They complement the text without dominating it, the way precise, overdrawn, four-color paintings in kiddie books always seem to be these days. The Burningham stylization makes the pictures somewhat reminiscent of Edward Gorey, although shading is mostly done by loose ink-wash rather than india-ink cross-hatching. As an example, see the below illustration, of two children with a baguette in a decrepit room.

I must emphasize, of course, that I am discussing only the Ian Fleming book here, and not the 1968 movie musical of the same name starring Dick Van Dyke. That film is a curious creation, too, but it has an almost completely different story, written by Roald Dahl. The film has a big, sentient motorcar that flies, but that’s pretty much it. The movie Chitty is set in a different era and landscape – part Edwardian England (à la Mary Poppins), part Brothers Grimm.

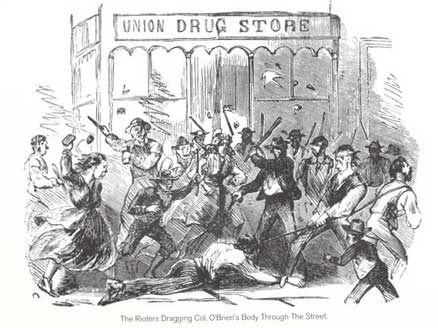

Dahl’s imagination had some parallels with Fleming’s, but was much crueler and more transgressive. For example, Fleming would never have come up with a horrifying figure like Dahl’s Child Catcher, who steals away Jeremy and Jemima and locks them in a mobile cage. In the Fleming version, the children are indeed kidnapped, but by stock movie villains out of a 1950s French gangster film, or maybe an Ealing comedy. And the gangsters give the children jam and baguettes for breakfast because (explains the author) that’s what you eat for breakfast when you are in Paris. Even though he’s writing about a flying car, Fleming keeps his tale recognizably rooted in Mother Earth.

Speaking of variant versions, if you want to read the real Chitty, be sure to hunt down an edition with those original John Burningham drawings, because it may not be available at your kiddie-book counter. Alternatively, take a glance at the “potted” version of the book featuring Burningham illustrations that Fleming’s nephew provided to the Guardian for Chitty’s fiftieth anniversary in 2014. Originally, Fleming wanted the political cartoonist Trog (Wally Fawkes), but Trog’s newspaper editor nixed the plan because Fleming’s work was usually serialized in a rival newspaper. This was an unexpected bit of luck. Nobody drew better than Trog, but Burningham’s ink-wash dreamscape was a far better choice for Chitty.

By all means shun any Chitty edition with some later dauber’s efforts – those overly colorful and hyper-detailed ones. And avoid like the plague those brummagem titles (Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and the Race Against Time, e.g.) that were cranked out by later authors, in much the same way that every writer from Kingsley Amis on down had to take a crack at writing a James Bond thriller after Ian Fleming died. Chitty is not a franchise. As the imitation Bond books demonstrate all too well, the Fleming wit is not susceptible to replication.

I keep dwelling on those original Burningham illustrations because they not only match the Fleming text, but they capture the grey 1950s sensibility that you get in the British cinema of the era. Off the top of my head, I think of the film version of John Osborne’s The Entertainer (directed by Tony Richardson), and Basil Dearden’s excellent The League of Gentlemen. Both films were released in 1960, but are set a few years earlier, so are pretty much contemporary with Fleming’s Chitty. They depict a squashed-down, etiolated England (or “Britain”), still listless and crippled from the War and Austerity. Vestiges of Imperial and martial glory still abound, but they are dusty and repellent, like Miss Havisham’s wedding cake.

The atmosphere is all very much Angry Young Men stuff, like Lindsay Anderson’s famous 1957 essay where he says, “Let’s face it; coming back to Britain is always something of an ordeal . . . And you don’t have to be a snob to feel it. It isn’t just the food, the sauce bottles on the café tables, and the chips with everything.”

In the Dearden movie, Jack Hawkins – that matchless cinematic colonel – gathers together a clutch of former officers and gentlemen (Bryan Forbes, Richard Attenborough, Richard Livesey, et al.) who did very well in the War, but not at all well since. One is a cuckold in an old-school tie who runs illicit gambling parties; one is a homosexual ex-Blackshirt who now works as a physical trainer; another is a fake clergyman with a string of sex scandals. The Jack Hawkins colonel treats them to a lunch in an upstairs suite at the Café Royal (it looks more like a catering room in Torquay), and reveals his master plan for a great bank robbery. Later, they are rehearsing the robbery plot in a script-reading room when a theatrical queen (a young, camp Oliver Reed) flounces in, looking for Babes in the Wood rehearsals. “No, we’re rehearsing Journey’s End,” Hawkins replies. Journey’s End, indeed; their country has let them down, and now Hawkins & Co. are going to get their own back, through esprit and ingenuity.

And this is the background theme to Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Commander Caractacus Pott (Royal Navy, like intelligence officer Ian Fleming) is a brilliant man and inventor, but has not done well for himself and his family. His inventions don’t catch on. The Potts are poor; they don’t even have a car. Then Commander Pott accidentally creates a candy that makes him a tiny fortune. They shop for a car. But the eccentric Potts doesn’t want to be like the other people they see, clogging up the motorway in their little black beetles. They must have a vehicle that is somehow special.

In a junkyard, an early 1920s racing car seems to call out to them, with the portentous license plate GEN II. This, of course, is Chitty Chitty Bang Bang herself (based on a bizarre, but very real racing car, Chitty Bang Bang, that young Ian Fleming recalled from the early 1920s). The old car was about to be sold for scrap. But Commander Pott buys her and, with a little bit of tinkering, gets her on the road. The family decides to go to the beach on a fine day, but they find the road clogged with thousands of the despicable black beetles. So Chitty spreads out her wings and soars above the lesser folk, landing on a lone beach available only at low tide. Then, Chitty and the Pott family “swim” the English Channel and end up in France, where adventures and gangsters await.

Ian Fleming wrote Chitty Chitty Bang Bang in the spring of 1961, and did it very quickly, because it was just a series of stories about a “magical car” that he had made up as bedtime tales for his son. Its publication in late 1964 coincided with the release of the Disney movie Mary Poppins. What curious antipodes of juvenile entertainment! Fleming’s subtle and inadvertent Angry Young Man critique of 1950s British society, coming up against a fanciful picture of a pre-1914 England, when everyone had a nanny, and the most visible revolutionary movement was Glynis Johns and her suffragettes.

But there was one beneficiary to this cultural collision. Fleming’s successor as kiddie-bestseller author was his friend Roald Dahl, whose entrée into children’s books, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, came out at almost the same time as Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Accordingly, Dahl was the obvious, immediate choice to write the Chitty movie script. And so Dahl wrote his mad and perverse – albeit commercially successful – film of Chitty. It had little to do with the original book, but it carved out for him a whole new career as a children’s author (James and the Giant Peach, Matilda, The Fantastic Mr. Fox, etc., etc.).

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory has been filmed twice. Surely it’s time for Chitty Chitty Bang Bang to get the film it deserves. Black-and-white. No songs. In the 1960 directorial style of Basil Dearden.

Photo: Caffé Gelato Vero, San Diego, September 1991

Photo: Caffé Gelato Vero, San Diego, September 1991

Or just plain old URL:

Or just plain old URL:

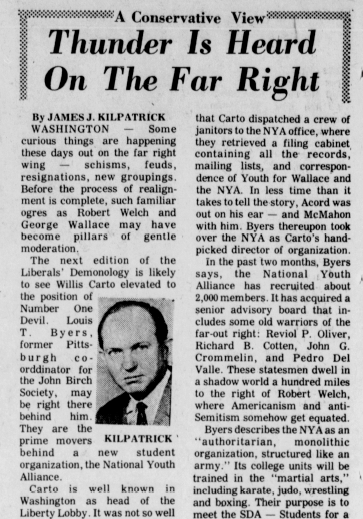

For me, one of the great takeaways from the Willis Allison Carto Online Presidential Library—actually it’s

For me, one of the great takeaways from the Willis Allison Carto Online Presidential Library—actually it’s