That title will make no sense to anyone born after about, say, 1975. But bear with me! We’re going to tell you a story of magazine publishing, mass media, Women’s Libbery, and sex talk over the last 50 or 60 years.

But first please take a tour with us in our Backstory…

Understanding Trade Advertising

A few years back I was trying to write an essay on the precipitous, seemingly never-ending decline and decay of TIME magazine. I was going to call it The Long, Grueling Downward March of TIME. The featured illustration would be a mockup of a title card from the March of Time newsreels, which of course were a big deal in the 1930s and 40s. Back when my average reader was growing up.

But it was a difficult topic to encompass, and I let myself get sidetracked by a curious side-story to the whole thing: magazines’ trade advertising, a now all-but-vanished industry.

Forty to sixty years ago you’d see ads at commuter railroad stations, and on the bulkheads (or whatever you call ’em) of passenger coaches on the New Haven RR. Also the Long Island RR, the NY Central’s Harlem and Hudson Lines, the PRR’s Paoli Local on the Philadelphia Main Line, and most probably the Erie Lackawanna out in New Jersey. Railroads had individual names then. They were clean and classy, they ran on time (usually), and they carried a lot of trade advertising for newspapers and magazines.

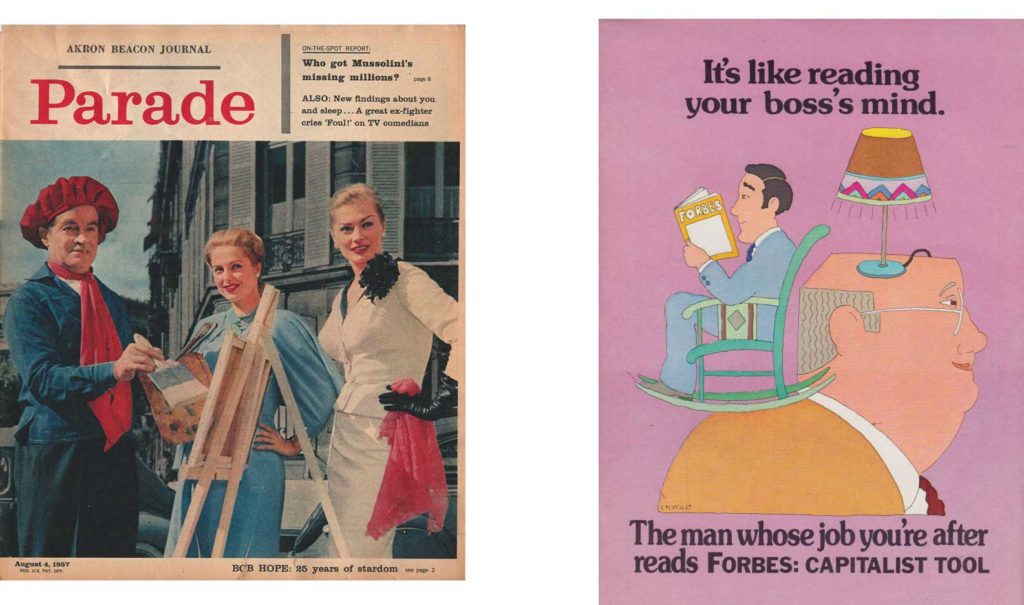

PARADE…is the Sunday Giant.

FORBES: Capitalist Tool.

Such advertisements weren’t aimed at potential readers of Forbes or, Lord knows, Parade (an extraordinarily lowbrow and popular newspaper Sunday supplement that lived for 80 years till it finally died a few months ago). No, these commuter-railroad ads were aimed at ad buyers, and maybe the sales people at the agencies, the people who called themselves “account executives.”

TIME magazine had perhaps the most elaborate trade advertising campaign of the late 60s, helmed by Young & Rubicam. You’d see a half-dozen, maybe even a dozen, poster ads out on the train platform. All in a row, all nearly identical mockups of a TIME cover, only with a different upscale TIME advertiser featured in each one. The copy would go something like: “TIME: Where Braniff Flaunts It.” Which in those days everyone knew was a reference to the big double-truck ads from Wells Rich Greene for Braniff Airlines, with the heading, “When You’ve Got It, Flaunt It!,” with a startling visual of, say, Andy Warhol chatting with Sonny Liston in Braniff first-class seats. (This was an era when most sentient people were expected to recognize advertising slogans, and so Mel Brooks put the Braniff line into his 1968 film, The Producers.)

Anyway, as you walked down the train platform, or glanced out the windows at Cos Cob or Bronxville, you’d get the message, over and over. TIME was where the smart money went. TIME was where you wanted to advertise high-ticket items to upscale customers. Braniff. MG 1100’s. Brooks Brothers suits. Johnny Walker Black. Lucchese boots.

Actually they never featured Lucchese. Ad buyers on the New Haven line in 1969 wouldn’t have understood that. Johnny Black they would understand, so if you were handling the campaign for Glenlivet, you’d look at the outdoor ads and be reminded that Johnny Black scotch had two full-page TIME insertions per month, while Glenlivet didn’t have any. And you’d think, “Maybe we should make TIME part of our media buy!”

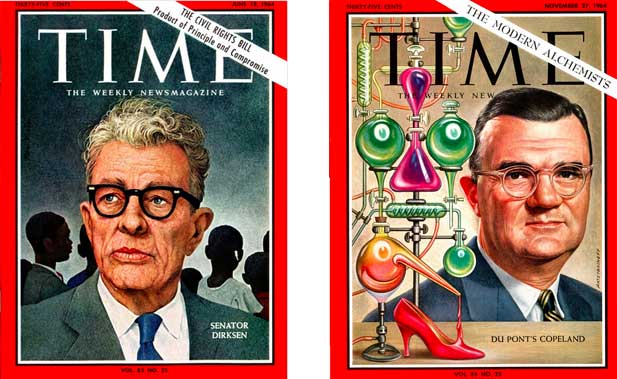

An implicit but unstated message in the TIME trade-ad campaign was that TIME was still a solid and trusted advertising environment. While Henry R. Luce (1988-1967) still lived, Time Inc. had been considered a gilt-edged, crack outfit, right up there with—as they used to say years ago—the Marine Corps, the Catholic Church, and McKinsey & Co. All of which may be well and thoroughly pozzed today, though none quite so badly as TIME, which was already in sorry shape in the 1980s when they started putting Madonna on the cover…instead of painterly portraits of Ev Dirksen or the DuPont CEO who gave us Corfam.

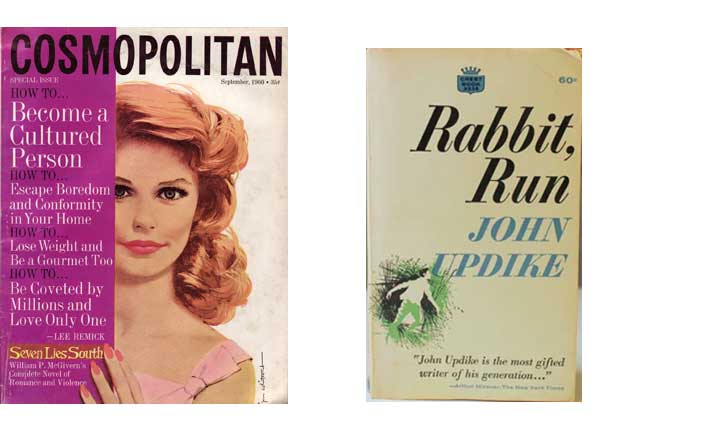

So much for this tangent. I’ll save my TIME eulogy for another time and place. Right now I’m going to move along to another classic bit of trade advertising from the same era, one that didn’t claim upscale status at all. In fact it reveled in being the vademecum of shopgirl and secretary. That was Helen Gurley Brown’s Cosmopolitan, an aggressively low- to middle-brow sex-and-makeup rag that came out of the Hearst Building on West 57th Street.

Diaphragms:

Or, the Transitional ‘Rabbit, Run’ Era of Sex Politics

Once upon a time, back in the 1910s and 20s and 30s, Hearst’s Cosmopolitan had been a popular family-type offering along the lines of the Saturday Evening Post, specializing in longish-form fiction (Agatha Christie, Jack London, Sinclair Lewis) and columns by name-brand celebrities (Gene Tunney, Amelia Earhart). This was all long gone by the 1960s, when editor Brown wrote Sex and the Single Girl, an early-Sixties bestseller on how to find the right man and get laid without necessarily getting pregnant. [1] After which, mid-Sixties, Brown revamped Cosmo, from an anodyne ladies-and-family rag into a celebration of working-girl licentiousness. “Career-girl freedom and sophistication,” Helen Gurley Brown might prefer to call it. But, as I say, the magazine’s target audience was secretaries and shopgirls.

If the magazine had had an iconic symbol in those days, it would be what doctors used to call a “pessary.” That is to say, a contraceptive diaphragm, less formally known as a “flying saucer,” according to John Updike. A round, flexible pink thing you stuck up your quim when you’d been to the singles bar and found yourself entering into a one-night-stand. (The you in this directive is female, needless to say.) Yes, a “birth control” device. It lived in a clamshell case in your top bureau drawer, or maybe at the bottom of your handbag, if you were out on the prowl. Often kept alongside some spermicidal cream or unguent. That’s enough detail.

I recall Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, in Updike’s Rabbit, Run, getting really pissed off when the girl he’s getting lucky with—part-time whore, as it turns out—runs off to the bathroom just as they’re getting started. “You’re gonna put on a flying saucer?” yells Harry. Harry hated the obviousness, the crassness of the whole thing: approaching sex or “lovemaking” as a mechanical necessity, an ugly physical function. You know, like going to the utility closet and taking out a Fleet Enema because you ate a lot of turkey stuffing at Thanksgiving and now you’re impacted and you’ll have huge difficulty taking a dump. Not exactly an arousing bit of foreplay.

The novel is set in the late 1950s. Perhaps 1959, as Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, is age 26, and that’s what author Updike was in 1959. So they both were born in 1933, in Reading, PA. Only in the book Reading is called “Brewer.” (Pennsylvania Dutch country, you see: they brewed beer.) John Updike wasn’t exactly like his protagonist. Harry Angstrom, a former high school basketball star, is a lower-middle-class guy with a nothing job, demonstrating MagiPeel Peelers in dime stores around Brewer; whereas Updike was then a young New Yorker writer who’d come out of Harvard. Rabbit, Run, which Updike originally began as a movie script, is a kind of “What if” contemplation on the author’s part: How shitty would my life be if I hadn’t gone off to Harvard? Would I be like some of those guys I went to high school with, who stayed in Reading?

Early in the book, the Mickey Mouse Club show is on TV and Head Mouseketeer Jimmie Dodd is carrying on about proverbs and ethical living. “Know thyself,” he tells the kids. “Know Thyself, a wise old Greek once said… God gives to each one of us a special talent.” Harry and his young drunken wife Janice watch this when Harry gets off work. Harry has contempt for the smarmy Head Mouseketeer but watches this intently, because Jimmie seems like a wise preacher or coach who might have useful advice about how to straighten out your life. Later on, when Harry and Janice drift apart, Harry looks for advice from a real-life Jimmie, in the person of a shallow, agnostic, wisecracking Episcopal minister named Rev. Jack Eccles.

I last read Rabbit, Run about 1969, and this is the kind of stuff that sticks with me through the years. Mouseketeers and diaphragms.

Today, pop social-historians will talk about birth control and tell you, “Diaphragms were totally passé after The Pill came in.” Not quite, hon. They were the go-to protection at least through most of the 1970s. Most of us weren’t going to do The Pill. Hormones? All those side-effects? Your breasts would swell. It might ruin your fertility long-term (though that risk wasn’t clearly understood or enunciated back in the day). Finally: maybe you won’t even have sex this year. And meantime your diaphragm’s waiting safe and sound in your bureau drawer.

“Female Empowerment,” Sort Of

And now we circle back to Cosmopolitan, which my social peers and I seldom ever touched. Cosmo was coarse, but put it down a marker. Getting laid a lot in the 1960s and 1970s became a sign of Female Empowerment, a term that did not yet exist, but should have. And here is where Cosmo led the parade.

Then, during its high-water mark in those late 60s, early 70s, Cosmo‘s man-catching “empowerment” ethos started facing down competition from a much fresher and weirder bit of popcult—Women’s Liberation! Women’s Lib ideology operated in much the same way as Cosmo‘s—you were supposed to spend a lot of time thinking about your private parts, and you were to strive for independence and assertiveness. Except man-chasing and singles bars weren’t much in the picture. A baby might occasionally turn up, but he usually had no visible father.

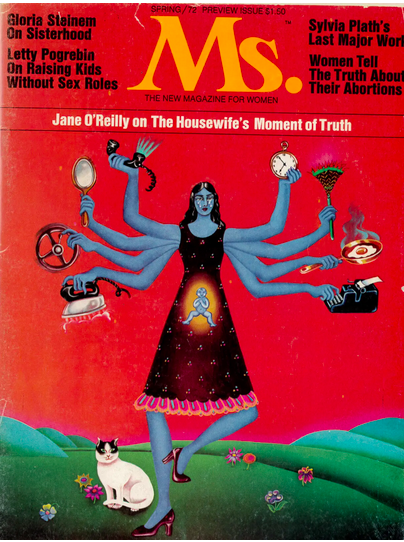

Cosmo seldom directly addressed this pop-culture conflict in its pages, so far as I know. When the Women’s-Libby Ms. magazine appeared in 1972, it didn’t acknowledge Cosmopolitan either. You could tell from the outset that Ms. wasn’t going to be anything like Cosmo. It wasn’t chuggy-jam full of makeup ads, and it didn’t have questionnaires and tips about sex and dating. And of course it didn’t have those garish, cat-in-heat Cosmo covers.

Cosmo seldom directly addressed this pop-culture conflict in its pages, so far as I know. When the Women’s-Libby Ms. magazine appeared in 1972, it didn’t acknowledge Cosmopolitan either. You could tell from the outset that Ms. wasn’t going to be anything like Cosmo. It wasn’t chuggy-jam full of makeup ads, and it didn’t have questionnaires and tips about sex and dating. And of course it didn’t have those garish, cat-in-heat Cosmo covers.

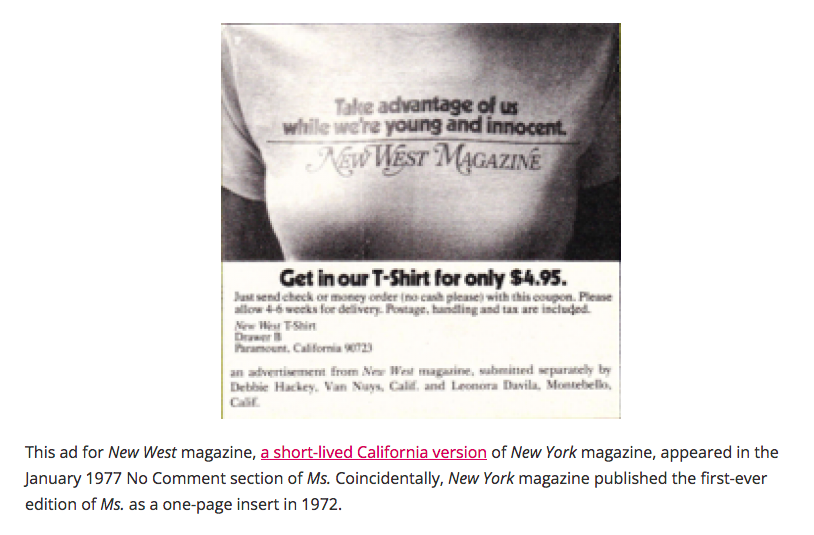

However one could argue that Ms. did take swipes at Cosmo in a very oblique way: it ran a page or section at the back called “No Comment,” displaying perversely funny instances of “sexism” in advertising and media. “Sexism” here usually meant showing a buxom, glamorous female model in an ad for t-shirts or limousine services or whatever. In other words, using sex to sell your product. Precisely the sort of come-on that Cosmopolitan used on its cover month after month.

So Cosmo editors and Ms. editors inhabited two different universes and neither side openly acknowledged the other. I don’t recall anyone ever remarking on this paradox. Even though both camps were selling a Career Girl persona that liked to imagine itself as “Fun, Fearless, Female”—to use a 1990s Cosmopolitan slogan. But the rivalry really wasn’t between two magazines. At its root was a fierce culture war that neither could really articulate. And this made for many amusing, unacknowledged ironies.

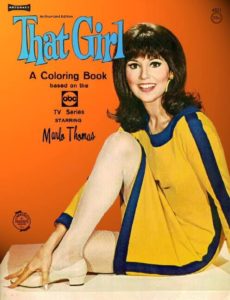

Ms. featured actress Marlo Thomas as a contributor in the early years, mainly in a running feature about children’s self-actualization and sex-role ambiguity. These bits were later collected in a book called Free to Be…You and Me. Now, Marlo Thomas was mainly known as the Danny Thomas daughter who landed the title role in a 1966-71 TV sitcom, That Girl. [2] In this sitcom, Marlo’s character, Ann Marie, was all about chic clothes, flip-hairdo, mascara-and-eyeliner, and being man-hungry and marriage-focused (though there weren’t really any marriageable men around, given that the men in Marlo’s social circles consisted mainly of Jews, elderly divorcés, and homosexuals).

Ms. featured actress Marlo Thomas as a contributor in the early years, mainly in a running feature about children’s self-actualization and sex-role ambiguity. These bits were later collected in a book called Free to Be…You and Me. Now, Marlo Thomas was mainly known as the Danny Thomas daughter who landed the title role in a 1966-71 TV sitcom, That Girl. [2] In this sitcom, Marlo’s character, Ann Marie, was all about chic clothes, flip-hairdo, mascara-and-eyeliner, and being man-hungry and marriage-focused (though there weren’t really any marriageable men around, given that the men in Marlo’s social circles consisted mainly of Jews, elderly divorcés, and homosexuals).

In other words, this sitcom actress, now playing on the Women’s Lib/Ms. team, was mainly famous for playing a character who was the veritable template of the Cosmo Girl! As the Cosmo ad copy went at the time (paraphrasing from memory here), “I’m 23, I’m a Gemini, I love to dance and snow-ski and listen to semi-classical music. I raise pedigreed longhair dachshunds, I’m fresh and funny, and I make a great chocolate fondue. I guess you could say I’m That COSMOPOLITAN Girl!”

A trade-ad version of the “Cosmo Girl” copy was refined into a text-heavy print advertisement that might take up a whole page in the New York Times, or a four-foot poster in a subway concourse. This copy had more word, more italics, with the final tagline, “If you want to reach me, you’ll find me reading COSMOPOLITAN.” The Cosmo Girl campaigns were widely enough recognized that in 1973 Donald Barthelme published a postmodern comedy takeoff in The New Yorker, “That COSMOPOLITAN Girl.”

Helen Gurley Brown sometimes called herself a feminist, and to the end of her life believed that she and Cosmo had helped to pioneer the Women’s Liberation movement. But attempts to express this always looked like comical misfires. Much like the Virginia Slims cigarette print ads and TV commercials of the early 70s. (“You’ve come a looonnnng way, baby!”)  For cigarette advertising, “women’s rights” meant that dames could now smoke skinny 100mm cigarettes in public.

For cigarette advertising, “women’s rights” meant that dames could now smoke skinny 100mm cigarettes in public.

For Cosmopolitan, it was all about young women being actively sexual and maybe promiscuous—we’ve got the Sexual Revolution now, baby, and The Pill! This was supposed to put them on a par with men, whatever that meant. Why they would want to be on a par with men remained the great unanswered question.

Why Ms. Failed

A great irony about Ms. magazine is that it was largely conceived and funded by Clay Felker, Gloria Steinem’s great & good friend, editor, mentor; and also founder of New York magazine. Ms. began with a big promotion from New York, while Clay and Gloria’s connections, including the best editorial and business brains of the era, seemed to guarantee its success. And yet…Ms. tanked…it ran in the red for many years and finally ended up as a squirrelly not-for-profit vanity operation that now barely exists as a website. This story deserves close examination.

In the early 1960s Clay Felker, a St. Louis boy (Webster Groves, MO), was associate editor of Esquire. Clay should have become top editor, but he lost out to Harold Hayes. A few years later he triumphed anyway, redefining the regional magazine business in the late by creating the brash, elegant, up-to-the-minute-hip New York. It was a hit from the moment of its launch in 1968. (Go to Google Books and look at early issues.) Its success spawned a series of imitators in the field of regional weeklies and alternative-news magazines and papers of variable quality…New Times! New West! Miami New Times! Phoenix New Times!, LA Weekly!…some of which exist even to this day.

New York magazine was the resurrection, or continuation, of a newspaper Sunday supplement. That was New York Herald-Tribune‘s magazine, also called New York, which Clay had also edited. Tom Wolfe, among others, got his start writing for that Sunday-supplement way back in the early Sixties. When the Herald-Tribune died in 1966-1967, as the result of a bad merger and massive newspaper strike, Clay Felker and some of his edit staff and stable of “New Journalism” writers—Tom Wolfe, Gloria Steinem, Jimmy Breslin—quickly got together and launched the glorious new standalone New York magazine.

A success from the start, as I say, as New York had both eye-grabbing design and no serious rival for advertising bucks. The New Yorker was the only other glossy weekly with a Manhattan focus. But after many years of William Shawn’s editorship it was now grey, somnolent, inward-looking; usually stuffed full of 40,000-word three-part John McPhee treatises on the history of barley or whatever, as well as obscurantist attempts at humor by Donald Barthelme. Apart from movie reviews and (sometimes) a Talk of the Town piece or a rare John Cheever or John O’Hara story, The New Yorker‘s editorial content was pretty much inaccessible. People got the magazine mainly for the cartoons and movie listings. Back in the late 60s we still had a movie house, maybe two, on every block of Midtown Manhattan. In those days a periodical could survive on running little more than movie and theater listings and ads. The weekday New York Times would have three or four pages of movie ads and reviews alone. To mention Tom Wolfe yet once again: he gained his first real notoriety in 1965, when he mocked editor Shawn and the stultifying dullness of The New Yorker, in the Herald-Tribune version of New York. (“Tiny Mummies! The True Story of The Ruler of 43d Street’s Land of the Walking Dead!” Story told here in a Wolfe obituary.) Serried ranks of aging writers came out of the woodwork to damn the audacious young popinjay, and the rest is history.

But to get back to Ms. For reasons I cannot now recall, Gloria Steinem had become a big deal in 1970 or ’71. From being a byline in New York magazine she became the uncrowned queen and default spokesman of the Women’s Lib movement. Her media-friendly looks had a lot to do it: she wasn’t a harridan or hippie-radical, and she had a trim figure and big, long, honey-brown hair. She was like a Cosmo girl who’d gone to Smith and once took a job as a Playboy Club bunny, just so she could write a jokey magazine article. And now, finding herself a “movement” leader, she thought she needed a publication, a mouthpiece to communicate with fans and supporters. Maybe, she thought—a newsletter!

This is where Clay Felker jumped in and told his old protégé, more or less, that the newsletter thing was the lamest idea he’d ever heard. Something like: No, Gloria! You must have a hot new hip magazine! Yes! And I will help you! What Clay imagined was a witty, snarky female version of Esquire. Clay had wanted to be top editor of Esquire back in 1961, but lost out to Harold Hayes. And now he would midwife, so to speak, a new, brainy, funny Esquire, only—you know, for the ladies! Maybe Clay would get New York/Esquire “New Journalism” writers to contribute. Gail Sheehy, Gay Talese, Susan Sheehan, Jimmy Breslin, maybe even Tom Wolfe!

Months before Ms. was officially launched, Clay promoted a mini pilot issue of 40 pages, stapled into a December 1971 issue of New York. The bloodline was apparent here, and in the early issues the following year. No bra-burner stridency here, but lots of hipness and irony. A light, supercilious attitude dominated.

Clay knew editorial and design, but maybe not the business side of magazine publishing. Furthermore, Gloria and the other Women’s Libbers in Ms. editorial not only did not know the business side, they were downright hostile to business and advertising in general. Ms. got the biggest, send-off any new magazine has ever had, and it could have sailed on high forever had it accepted ads from Lancôme and Bergdorf-Goodman, but Gloria and colleagues decided they absolutely did not want advertising for cosmetics or fashion.

Clay knew editorial and design, but maybe not the business side of magazine publishing. Furthermore, Gloria and the other Women’s Libbers in Ms. editorial not only did not know the business side, they were downright hostile to business and advertising in general. Ms. got the biggest, send-off any new magazine has ever had, and it could have sailed on high forever had it accepted ads from Lancôme and Bergdorf-Goodman, but Gloria and colleagues decided they absolutely did not want advertising for cosmetics or fashion.

In fact, they didn’t want most female-oriented advertising. I suppose they were afraid of looking like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. They had it in their heads that fashion and cosmetics were the problem, the enemy of Women’s Libbery. Gloria probably didn’t think that, but as with the Bolsheviki, she had to accommodate the angriest, most extreme factions in the party.

Hence, the financial failure of Ms., one of the greatest paradoxes and fiascos ever, in magazine publishing. It’s as though Esquire were to reject ads for sports cars and golf clubs and scotch.

Another problem, on the editorial side, was that there were militants at the magazine who were mainly focused on navel-gazing issues of Women’s Lib. A big one in those days was, “Can we let lesbians into the Movement?” Ironical to consider today, but it was serious in the early 1970s. There was also cheerleading for abortion—pretty easy to obtain pre-Roe v. Wade, but they moaned about restrictions anyway. (Plus ça change. The current iteration of online Ms., led by octogenarians, is still obsessed with the need for free and easy abortion.)

And the Ms. staff would ask themselves, “Can we let men write for Ms.? I gather they gave a resounding no on that one. Just as they didn’t want male editors or business staff. So, no cover stories by Tom Wolfe. For that matter, no Gail Sheehy, either. She and Clay Felker had become an item—they would eventually marry in 1984—and they could see that the Ms. editorial board had determined to drive the magazine into the ground.

Only one spark of Clay’s original concept remained, and that was the notion that Ms. should have humor. This effort was relegated to that “No Comment” page, which mainly complained about “sexism” in advertising. Poor Clay himself got the shaft here in 1977, when his newly launched New West magazine (West Coast version of New York) ran a cut-rate subscription ad featuring a young lady’s poitrine tightly clad in a New West Magazine t-shirt. “Take advantage of us while we’re young an innocent.” And so it was slammed in the “No Comment” page.

The below Ms. commentary describes the Clay Felker/New York contribution to Ms. as a “one-page insert in 1972” when it was actually a 40-page mini-mag stapled into New York in December 1971. Gratitude is indeed just a word in the dictionary, and it does not lie sweetly with forgetfulness.

By 1987 Ms. it was seriously in the hole, and got passed to a series of owners trying to turn it around. Today it’s just a website that purportedly publishes a print quarterly. You can blame Ms.’s political advocacy for its failure, although obscurantist political missions don’t need to be fatal for a magazine. After all, National Review was always a money-losing operation, surviving year-to-year on gifts and grants and subsidies from the Buckley family. NR‘s bean-counters eventually figured out that they could shore up finances with such devices as selling tickets to $5000 shipboard cabins on celebrity-speaker cruises. This option, however, was never a likely one for the Ms. audience.

Moreover, Ms.’s editorial mission was very confused. Editorial content had less and less to do with its original core target audience (middle-class white American women), as the magazine started to fill up its pages with all sorts of extraneous topics, about foreigners and politics and People of Color, usually slanted from a progressive-Left angle. No more wit, hipness, irony. This was perhaps inevitable. There was a limited amount of subject matter directly relevant to Women’s Libbery, or even that amorphous, shifting cluster of grievances called “feminism.”

Moreover, Ms.’s editorial mission was very confused. Editorial content had less and less to do with its original core target audience (middle-class white American women), as the magazine started to fill up its pages with all sorts of extraneous topics, about foreigners and politics and People of Color, usually slanted from a progressive-Left angle. No more wit, hipness, irony. This was perhaps inevitable. There was a limited amount of subject matter directly relevant to Women’s Libbery, or even that amorphous, shifting cluster of grievances called “feminism.”

I once worked, briefly, on a strange website called Women’s Media Center. The content had almost nothing to do with broadcasting media, or with normal American women. About every featured personage was a “person of color” or Jewish (excuse me; Jane Fonda did turn up occasionally). and the topics under discussion were things like, “How Can We Get More Latina Anchorwomen?” I look at this website now, and it is still that way. Any outlet that makes its mission and purpose the promotion of a “progressive” ideology will inevitably go down this path of militant, ineffectual, fury. Likewise, Ms. magazine still exists, but only notionally. It makes no money, carries no ads, and no one I know reads it.

One can only wonder what would have happened if Clay and Gloria had managed instead to launch an “Esquire for Women.” They had the potential advertisers, and they had the editorial and advertising connections (via New York). Not so lucky was a later magazine called New York Woman, launched in the 1980s, conceived as an “Esquire for women,” and actually published by the Esquire parent company. It was witty and excellently designed. It was free of strident Leftism and Libbery. It was advertising-friendly. Alas, it couldn’t pull high-ticket ads because it never got much visibility or circulation, or a celebrity editor. Perhaps it didn’t have a definable audience. And finally, the failure of Ms. had probably ruined the market for this sort of thing. So New York Woman turned out to be just another showcase. It survived for a while because American Express Publishing took it under its wing, along with its Travel+Leisure and Food & Wine. But it never got the kick-start that Clay Felker’s publicity chops, and Gloria Steinem’s celebrity, were able to give Ms. in the early days. Most people reading this will never have heard of it. Nevertheless it lasted six years (1986-92), and it did better stuff in those six years than a whole half-century’s worth of Ms.

Unseen Adversaries, Inchoate Theories

As I said before, the culture war between the Cosmo camp and Ms. faction was seldom acknowledged because the two sides were virtually oblivious to each other’s existence. One was firmly rooted in a culture of working girls who used sexual wiles and gossip to gain power. It didn’t start with the 1950s. Early 1930s “Pre-Code” films are littered with instances of Jean Harlow, Clara Bow, Barbara Stanwyck sleeping their way to the executive suite. And not to be an executive, mind you! Sometime Vanity Fair editor Clare Boothe Luce did a slightly later, slightly more sanitized version of this immoral fable in The Women (1936 play and 1939 movie).

So that was the Cosmo camp. The other faction was rooted in journalism, academia, and abstruse theorizing about social dynamics and sex roles. One of their leading tenets was that sex roles are not innate but are learned. According to Socialization Theory, people are born as tabulae rasae but are socialized to be male or female. Presumably, if you’re an only child with neglectful parents who don’t socialize you, you get to end up as neither sex. This bizarre theory was propounded as serious feminist sociology and psychology fifty years ago. It is still advanced today, in many a cultural-marxist fever-swamp.

Hang out with progressive self-described feminists on social media, and you quickly see arguments telling you how Obnoxious Male Behavior is the result of Socialization. You know—how they send 5-year-old boys off to Socialization Camps. Sort of like Parris Island in ’42, I guess, where they have to climb the water tower and go, “This is my rifle, This is my gun…” and other sorts of hazing and bullying.

Other persistent myths and conspiracy theories from those days include the notion that Men oppress Women, and that this is because of a Patriarchy Culture that must be dismantled. Actually you didn’t hear so much about Patriarchy back the old days; that term seems to have been dusted off and shined up in recent years because of the rise of critical theory in academia.

Patriarchy theories couldn’t get much traction In the 1960s and 1970s because back then most people were still conversant with a social culture in which most people were expected to get married, and have babies, and it was generally the female parent who ruled the roast. (Yes, the word is roast, not roost.) If you alter that arrangement—take the mother out of the picture—you have the basis for a situation comedy, because having the father stand in for both parents is inherently humorous. Even in savage jungle tribes, it’s the old females, not the silverback males, who demand that the young females be brought before them to be de-clitorized and de-labialized, with their vulvas sewn up. Ain’t Matriarchy a gas?

The social and cultural divide between the two camps could never be breached. Many a teenage girl of this era affected a distaste for fine clothes and grooming, lest she be mistaken for a dim-bulb Cosmo reader. Back in the 1970s, did you see a lot of girls at Smith or Mount Holyoke going around in cargo pants or white painters’ overalls, with scraggly, unwashed hair in the 1970s? Well, if you didn’t see them, that’s how it was. The fear of Cosmo-world propelled some of them into disheveled lesbianism, or performative lesbianism, or at least priggish spinsterhood.

It’s the same mentality that today makes otherwise intelligent women believe that the television series of The Handmaid’s Tale describes an actual, possible future in which women will somehow be enslaved and oppressed by the likes of Amy Coney Barrett and Brett Kavanaugh. (Actually the original Margaret Atwood novel was a dystopian satire, mocking 1980s Leftists’ fear of Evangelicals and the Moral Majority.) While that is a confused, delusional way of thinking, it is useful for mindless sloganeering, in a sense someone like George Orwell would have understood. Better to die single and childless, many a middle-class, well educated young woman must have mused in the last fifty-odd years, than to focus on Hunting for a Man—as though I were a Five Towns JAP or a Cosmo floozy!

So which was worse, Ms. or Cosmo? I tend to think that Cosmopolitan did far more to ruin relations between the sexes than Ms. or mainstream “Second Wave” feminism ever could. It made the heterosexual dating game tawdry and distasteful. It made catching a spouse (and seeking a home and family) something anyone should sneer at, if her ambitions were anything above the level of stewardess or cocktail waitress. And thus we raised a whole generation of girls, women—under this pervasive yet unnatural mindset.

I recall, in the 80s, being asked by strangers if I were seeking a husband or looking forward to raising a family. I would go into an absolute cringe. What did they think I was? The sort of bimbo who read Cosmopolitan?

Facebook Comments