Document thief Barry Landau got a raw deal in 2012—from the press, the judge and Rod Rosenstein.

From the Federal Correctional Center in sunny Lompoc, California comes news that my old pal Barry Landau has been released. Oh wait—not quite. It turns out he’s just been transferred to a halfway-house in Riverside, and has a few months left on his bid.

This semi-prison is one of those private-contractor outfits that specialize in rehab and prisoner “re-entry,” but strangely enough (and unlike the Federal pens) it doesn’t let its wards use e-mail. So Barry and I are playing telephone tag right now and soon I’ll know when he’s getting out.

Barry Landau, you will recall, is the White House party animal and self-styled “Presidential Historian” who got arrested in Baltimore in 2011 while he and an accomplice were filching archives from the Maryland Historical Society. The Baltimore documents weren’t terribly exciting—e.g., 1881 presidential Inauguration programs. But then a Federal raid on Barry’s apartment in New York turned up a trove of choicer nuggets, lifted from a half-dozen historical libraries. A letter from Ben Franklin, an inscribed volume from Karl Marx, a note from Marie Antoinette, the autograph of Christopher Columbus.

That made it more than small-time local museum theft. A federal case was opened, by none other than Rod J. Rosenstein, now U.S. Deputy Attorney General, but then the U.S. Attorney for Maryland.

Barry and his young accomplice, Jason Savedoff, had a routine. They’d research an institution’s holdings online and draw up a wish-list. Then they’d show up, wreathed in smiles and bearing a plate of cookies or cupcakes for the library staff. Barry would schmooze personnel and distract them, while Jason pocketed precious paper.

The usual ruse was that Barry would show up at a library or museum and announce himself as an historian researching a new book. This seemed plausible. A few years earlier, Barry had published a lavish coffee-table book about White House banquets (The President’s Table: 200 Years of Dining and Diplomacy), and this got him appearances on C-SPAN, 60 Minutes, Martha Stewart, Today Show, etc. etc., as an erudite foodie-historian. Nevertheless his CV was odd for an scholar—“America’s Presidential Historian,” his website proclaimed him. He’d spent most of his career as a celebrity publicist.

Eight or nine years ago, when I was at Food & Wine magazine, I became aware that this neighbor of mine had somehow reinvented himself as a fine-dining expert. Sometimes I’d see him in our apartment building’s elevator or lobby, dressed in a souvenir roadie jacket from some Clinton Administration beano. “So you know Bill Clinton, then?” I asked.

“I’ve known lots of Presidents. Almost every one since Eisenhower!”

* * *

It was during Barry’s second visit to Baltimore (July 11, 2011) that a Maryland Historical Society staff member got suspicious and called the cops. Police and staff found up sixty MHS documents in a museum locker. The next day, they raided Barry’s New York apartment.

Initially the press treated it all as a big joke, a man-bites-dog story. “At the Maryland Historical Society, they’re calling it the Great Cupcake Caper,” wrote the Baltimore Sun (July 12, 2011). “Before being arrested by police on Saturday and charged with stealing dozens of historical documents, author and collector Barry H. Landau had brought cupcakes for the center’s employees. They figure he was trying to ingratiate himself with the staff, much as he has for decades with political and Hollywood elite.”

Indeed, the Cupcake Bandit had been a demi-celebrity for most of his life. Barry Landau turns up, Zelig-like, in old news and stock photos, with George Hamilton, Cheryl Tiegs, Tom Selleck, Patricia Neal, George Plimpton, the Bushes, the Reagans. Andy Warhol mentions him 20 times in his Diaries, usually rather sniffily. (“Barry Landau, that creepy guy we can’t figure out, who somehow gets himself around everywhere with every celebrity.”)

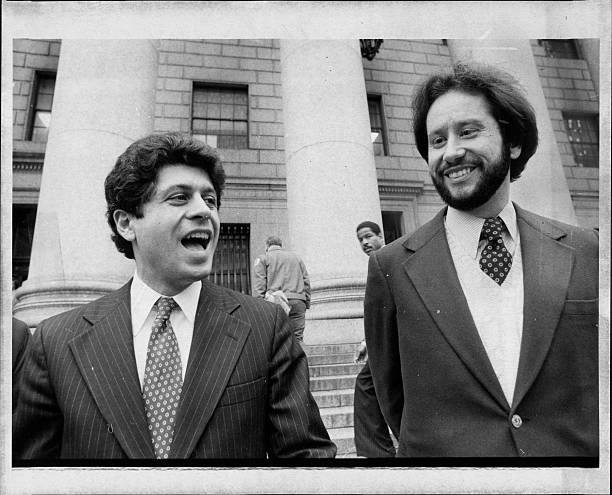

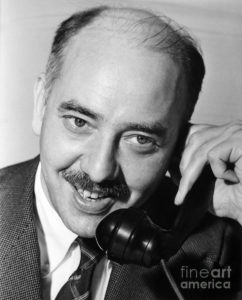

NY Times, 1979

In 1979 Barry’s picture was in the New York Post and NY Times for grassing on Hamilton Jordan, President Jimmy Carter’s chief of staff. Barry claimed to have seen him trying to score cocaine at Studio 54. This led to grand jury investigations in which 30-year-old Barry was a star witness, under the guidance of a bushy-haired young attorney named Andrew Napolitano.

But could Barry Landau really, truly be the mastermind of the Cupcake Caper? That looked unlikely at the outset. His lawyers denied it. They said Jason Savedoff was to blame. They portrayed the 24-year-old “aspiring model” from Vancouver BC as a persuasive, greedy Svengali. Savedoff had wormed his way into Barry’s confidence, and then used “America’s Presidential Historian” as a front-man to gain access to valuable archives. Unlike Barry, Jason wasn’t interested in history, or presidents; he just wanted to steal a lot of autographs and make a lot of money.

But could Barry Landau really, truly be the mastermind of the Cupcake Caper? That looked unlikely at the outset. His lawyers denied it. They said Jason Savedoff was to blame. They portrayed the 24-year-old “aspiring model” from Vancouver BC as a persuasive, greedy Svengali. Savedoff had wormed his way into Barry’s confidence, and then used “America’s Presidential Historian” as a front-man to gain access to valuable archives. Unlike Barry, Jason wasn’t interested in history, or presidents; he just wanted to steal a lot of autographs and make a lot of money.

But as the months rolled on, the media soured on Barry, and convicted him in the press long before the trial date. On TV and in the newspapers they’d show old file photos of him beside his vast horde of presidential memorabilia—acquired honestly over a half-century, ever since he first met Ike and Mamie Eisenhower in the 1950s—and insinuate that his 17th-storey corner apartment was an Ali Baba’s cave of stolen archives.

They’d write that Barry had grossly exaggerated his experience as a publicist and White House event manager. Famous names got phoned up for snotty comments. (“He was a name-dropper,” sniffed Barbara Bush.) And inevitably such outlets as The Daily Beast would speculate snarkily about the nature of the relationship between Landau and Savedoff.

Thus in the end it was Barry who got a ten-year sentence (7 years prison, 3 probation), while pretty young Jason got off with a slap on the wrist (one year in prison). At his trial in Baltimore, Jason’s attorneys drew a portrait of a pathetic, mentally ill youth who believed “conspiracy theories”; a naive kid who got hoodwinked by a worldly old reprobate.

This “victim” argument was probably inevitable; it’s an accusation that requires no proof, as was illustrated recently with the lurid, ludicrous rape tales aimed at Justice Brett Kavanaugh; or as we keep seeing over and over with the ancient, transparently fake “clerical abuse” stories.

But the Jason-as-victim argument looked brazen and presposterous. It came at the end of many months in which the consensus among press and prosecutors was that Jason Savedoff was a pathologically dishonest male hustler.

Barry’s sentence amazed me. How in hell does a 63-year-old first-time offender get a ten-year sentence for a non-violent crime? A crime, ladies and gents, in which most of the stolen goods were recovered—and (a crucial but overlooked point) had little historical significance. Most of them were ephemera—tickets, programs, cartes-de-visite—or autographed letters from the junkier end of the antiquarian world, the equivalent of a baseball signed by Mickey Mantle.

You don’t send an old guy to prison for seven years because he was an accomplice in the theft of a mint 1940 copy of Batman Comics #1.

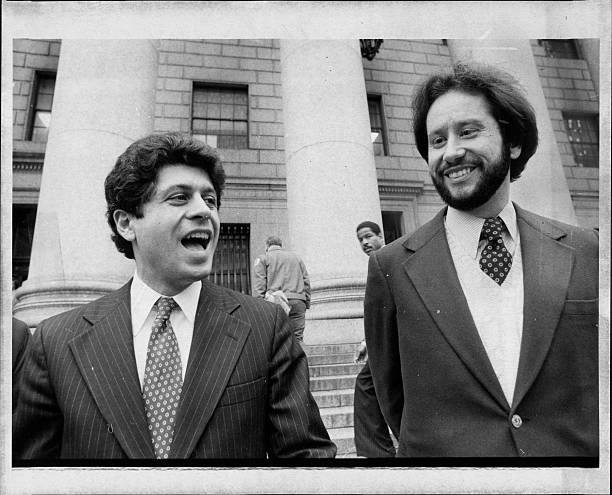

At Studio 54 with Phyllis Diller, 1979.

Did Barry have the worst legal representation in the world? I don’t think so. I think Barry and his counsel got conned. Rosenstein’s office did a bait-and-switch on them.

When the case began, Barry could have had a jury trial. He could even have pled not guilty because of extenuating circumstances.

Rosenstein’s office didn’t want that. That would be blaming the thefts on Jason Savedoff, and Jason Savedoff’s testimony was the whole foundation of their case. His allegations would never have stood up under cross-examination.

And so Rosenstein’s office . . . lied. The prosecutors offered Barry a deal: they promised leniency if he pled guilty, and waived that jury trial, with right of appeal. They told him the trial would be over quickly, and that Barry wouldn’t have to serve much time in prison.

And then, instead of giving Barry a suspended sentence or maybe a year (like Jason) they threw the book at him. And he couldn’t even appeal the verdict, because he signed that away when he signed the plea agreement.

Is there a murky backstory to all this? Did Rod Rosenstein have some personal interest in the case, perhaps on behalf of a friend? I don’t know, but his discussion of it was most peculiar and bespeaks a personal grudge. On television and in press releases, he repeatedly referred to Barry as a “con man” or “con artist.” Here he is announcing the verdict in 2012: “Barry H. Landau was a con artist who masqueraded as a presidential historian to gain people’s trust so he could steal their property.”

A con artist? There was no con or flim-flam involved here. Barry wasn’t taking people’s money for swampland deeds or forged documents. He didn’t masquerade as “presidential historian Barry Landau,” that is who he really was, with a big book and everything!

If he did in fact steal or misappropriate original documents . . . okay, that is not a transgression unknown among professional historians. But that’s not being a flim-flam man.

Rod Rosenstein’s choice of words is revealing. It suggests that Barry Landau’s real crime was not helping Jason Savedoff steal historical bumpf, rather it was having been a show-off, a social-climber, a celebrity hanger-on, a name-dropper (yeah; as Mrs. Bush said). The kind of person who would crash Andy Warhol parties and boast about seeing Hamilton Jordan try to buy cocaine.

Of course there might be some other, specific offense from the olden days that Barry had to be punished for. I just don’t know yet, dear readers. But I think it’s pretty safe to say he wasn’t sent on a long prison stretch just for lifting some ephemera from museums.

But could Barry Landau really, truly be the mastermind of the Cupcake Caper? That looked unlikely at the outset. His lawyers denied it. They said Jason Savedoff was to blame. They portrayed the 24-year-old “aspiring model” from Vancouver BC as a persuasive, greedy Svengali. Savedoff had wormed his way into Barry’s confidence, and then used “America’s Presidential Historian” as a front-man to gain access to valuable archives. Unlike Barry, Jason wasn’t interested in history, or presidents; he just wanted to steal a lot of autographs and make a lot of money.

But could Barry Landau really, truly be the mastermind of the Cupcake Caper? That looked unlikely at the outset. His lawyers denied it. They said Jason Savedoff was to blame. They portrayed the 24-year-old “aspiring model” from Vancouver BC as a persuasive, greedy Svengali. Savedoff had wormed his way into Barry’s confidence, and then used “America’s Presidential Historian” as a front-man to gain access to valuable archives. Unlike Barry, Jason wasn’t interested in history, or presidents; he just wanted to steal a lot of autographs and make a lot of money.

Abstract: After a decade or more of intense Diversification, American Girl Dolls actually added a (white) American girl to its lineup this year. Alas, it’s just an imitation Taylor Swift named Tenney Grant.

Abstract: After a decade or more of intense Diversification, American Girl Dolls actually added a (white) American girl to its lineup this year. Alas, it’s just an imitation Taylor Swift named Tenney Grant.